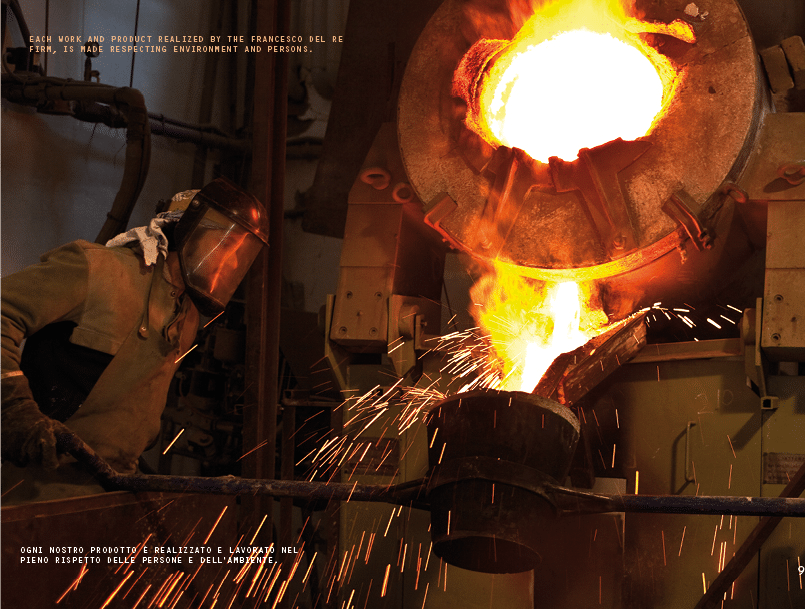

As the days grow shorter, and we inch toward the certainty of a cold winter, it seems fitting to talk about fire. I love fire. It takes a deep understanding of this primary element to master the process of “firing” clay. In my last installment we talked about frost proof ceramics and even that conversation must begin with a discussion about fire.

Clay begins as granite, decomposes and compressed for a millennia, then becoming a sticky, malleable mud with memory. When it passes through human hands, turning it into functional art… the real fun begins: the firing. Once the clay morphs all the way back to stone, it changes from stone to mud and back to stone again, transformed by fire. I feel lucky to be in the middle of this cycle, the one that gets to instruct the clay. Kind of a big responsibility really, manipulating the earth while it regenerates itself.

It takes a lot of heat to fire ceramics and even more heat to fire clay to vitrification (refer to Baked Earth installment How It Works: Frost proof Terracotta). Firing clay depends on what material we burn. This is why so many ceramic wares are under-fired: limited combustibles. In the developing world many traditional peoples have to travel further and further to harvest the wood or brush. As the forest recedes, they begin to use less fuel to burn the clay, because transportation is more difficult. Travel can take three or four times what it used to for procuring wood, or other combustibles, to fire the pottery, cook and heat their homes.

In the US, you will see many types of firings: wood, salt, recycled automobile oil, sawdust, dung, natural gas, propane, passive solar, and electricity. We are fortunate to have so many options within reach when it comes to firing pottery. Regardless of how the work is fired, some basic transformations occur on the clay’s long journey back to stone.

At 212°F the water in the clay converts to steam and is slowly released. At approximately 400 °F, all organic matter in the clay has burned out, and the cristobalite (a crystalline form of silica found in all clays) suddenly shrinks. Between 1000°F and 1100°F the quartz crystals change from an alpha crystal structure to a beta structure. Referred to as Quartz Inversion, the temperature must increase gradually.

From 1500°F to 1650°F, “sintering” begins. This is the stage where clay particles begin to cement themselves together to form a hard material called ceramic. From this point on, depending on the temperature range of the clay, vitrification occurs. For earthenware clays, this happens at approximately 2050°F. For stoneware clay, about 2300°F, and for porcelaneous clay, 2500°F.

The transformation of clay from stone and full circle back to stone is a long, hot journey that no other material makes. And here’s a little point of reference: Kilauea, the volcano on the big island of Hawaii, spewing lava into the Pacific Ocean was recently tested for temperature. The orange lava is only 1800°F—low fire in the world of clay!

See you next month!

I didn’t know about a lot of things that this articule says and I find it very interesting, how is the process of clay and how to finish a peace and all of the temperatures to use to make a perfect piece, the transformation of clay and everything. I really like the article.

Thanks for checking our blog out, Paulina!

-Eye of the Day Garden Design Center