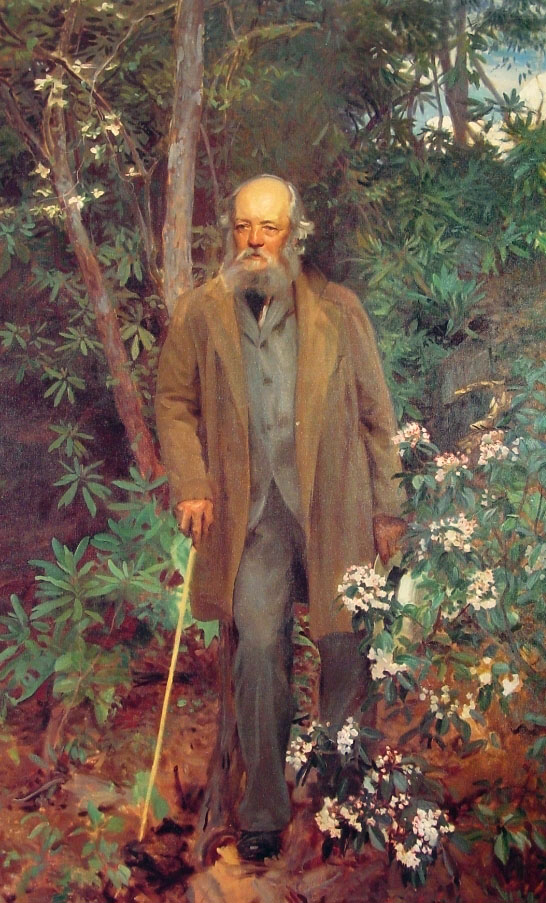

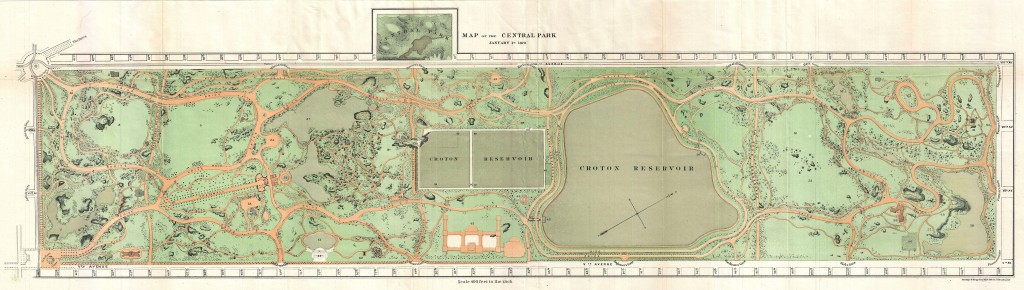

Frederick Law Olmsted, the father of American landscape architecture, is in many ways responsible for the way America looks. Beginning in 1857 with Central Park in New York City, he created designs for thousands of landscapes, including many of the world’s most important parks. Prospect Park and Fort Greene Park in Brooklyn are designed by Olmsted, as well as Boston’s Emerald Necklace, The Biltmore Estate in North Carolina, Mount Royal in Montreal, the grounds of the U.S. Capitol and the White House, Washington Park, Jackson Park and the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. Many of the green spaces that define towns and cities across the country are influenced by Olmsted.

1) Respect “the genius of a place”

Olmsted wanted his designs to stay true to the character of their natural surroundings. The goal was to “access this genius” and let it infuse all design decisions.

2) Subordinate details to the whole

There was no room for details that were to be viewed as individual elements. In his work, they were threads in a larger fabric.

3) The art is to conceal art

Olmsted believed the goal wasn’t to make viewers see his work. It was to make them unaware of it. To him, the art was to conceal art. And the way to do this was to remove distractions and demands on the conscious mind. Viewers weren’t supposed to examine or analyze parts of the scene. They were supposed to be unaware of everything that was working.

4) Aim for the unconscious

His designs subtly direct movement through the landscape. Pedestrians are led without realizing they’re being led. There is the sensation of feeling lost yet completely confident that you can easily return to your starting point.

5) Avoid fashion for fashion’s sake

He felt popular trends of the day, like specimen planting and flower-bedding of exotics, often intruded more than they helped.

Olmsted had no formal design training and didn’t commit to landscape architecture until he was 44. His views on landscapes developed from traveling and reading.

7) Words matter

Olmsted wrote often and thought hard about the words he used. For example, he rejected the term “landscape gardening” for his own work since he felt he worked on a larger scale than gardeners.

8) Stand for something

His writings show that, in his view, he wasn’t just making pretty, green spaces, he was democratizing nature.

9) Utility trumps ornament

He wrote, “So long as considerations of utility are neglected or overridden by considerations of ornament, there will be not true art.”

10) Never too much, hardly enough

He constantly simplified the scene, clearing and planting to clarify the “leading motive” of the natural site. Thirty years after he helped to design Central Park, he wrote to his ex-partner, Calvert Vaux, “The great merit of all the works you and I have done is that in them the larger opportunities of the topography have not been wasted in aiming at ordinary suburban gardening, cottage gardening effects. We have let it alone more than most gardeners can. But never too much, hardly enough.”

Olmsted believed in the restorative power of landscape for ordinary people. He disliked straight lines. He loved contrasting textures, but it was a cardinal rule with him to blur the boundaries. The architecture of Europe impressed him, but trees were his true love. And that true love shows. Everywhere.

SUZI — Liked your little synthesis of Olmstead’s principles. I went to a school in New Jersey in the 1950s that was designed by Olmstead: The Lawrenceville School —It was beautiful then and

remains so today. And there has been a lot of building there since my time. Which is saying something. He also designed the original Stanford campus, which today is appalling in its loss of face to surrounding monstrosities. HENRY

Dear Henry,

That sounds awesome! Thank you for reading and Suzi appreciates your thoughtful comment.

Best,

Joyce – Social Media/Marketing

To understand these principles is to be a practicing landscape architect in today’s world!